Same Old Game

"SAME OLD GAME! - The Barings' Crisis of 1890" Risk and Reward

Researching and writing “Same Old Game!” did not start from an interest in bankers or banking, but came from a local story in Devon, England where my wife and I have lived for several years. We were walking the South West coast path along a section that had been described to us as Lord Revelstoke’s carriage drive. A passing interest in who Lord Revelstoke might have been and why he should build this splendid drive led to a series of connections which took me back in time to Philadelphia in 1774 and the first Continental Congress, and the close connection between Barings Bank and the birth of the American nation. That research resulted in “Merchants of War”, a history that comes to an end in 1810, but sets the scene for its sequel, “Same Old Game!” So with the early history of Barings now assimilated, I went back, or rather forward to the story that triggered my interest in the first place, and returned to Lord Revelstoke - Edward Charles Baring, who had acquired the Membland Estate in south Devon in 1877, whilst he was senior partner of Baring Brothers Bank. His cousin and fellow partner in the Bank, Henry Bingham Mildmay, had acquired the adjacent estate of Flete the year before. The two men had married, by coincidence it seemed, sisters who had grown up at Flete before the estate (and that of Membland) had been lost to their family through some distant financial disaster. The question of why the two London bankers would marry the two Devon sisters was still hanging when I read more of the Barings Bank crash of 1890 – the one that preceded the Nick Leeson affair by almost 100 years, and in its time of equal magnitude, if not with quite such devastating results. Barings Bank crashed in 1890 because of one speculative investment too far in Argentina – the partners seemed somehow distracted in Devon. Only reluctant but decisive action by the Bank of England with support from, amongst others, Lord Rothschild saved a run on the world’s Banks. Barings was a private merchant bank and its liability was unlimited. The quid pro quo imposed by the Bank of England on the partners, in particular Edward Charles Baring and Henry Bingham Mildmay, was draconian – in effect putting both men into bankruptcy, and requiring the disposal of the Devon estates, the Mayfair townhouses and the sale of their sumptuous contents. I have attempted to describe what has become known as the “Baring Crisis of 1890” together with the stories of the four very different families that came together to participate in a real-life Victorian melodrama, complete with its a tragic finale. To do this I have split the book into three parts. Part 1 chronicles the families, Barings, Bulteels, Binghams and Mildmays; Part 2 the ”Baring Crisis” itself, and Part 3 deals with the aftermath of the event. I have attempted to keep the story flowing to make to make it easier to read. However the wealth of background research that has been assembled cannot be ignored, so for more information on any aspect of the story, hopefully you will find it the “Notes and Sources” section that is classified by chapter, or in the appendices. Barings Bank did recover from the crash of 1890, only for history to repeat itself almost 100 years later, when Nick Leeson killed it off once and for all, after the lessons learnt at the end of the nineteenth century had long been forgotten. If you do ever get to walk the carriage drive at Noss Mayo in Devon you will you will know who built it and what became of him! And here it is – I hope you enjoy “Same Old Game!” as much as I did researching and writing it!

Researching and writing “Same Old Game!” did not start from an interest in bankers or banking, but came from a local story in Devon, England where my wife and I have lived for several years. We were walking the South West coast path along a section that had been described to us as Lord Revelstoke’s carriage drive. A passing interest in who Lord Revelstoke might have been and why he should build this splendid drive led to a series of connections which took me back in time to Philadelphia in 1774 and the first Continental Congress, and the close connection between Barings Bank and the birth of the American nation. That research resulted in “Merchants of War”, a history that comes to an end in 1810, but sets the scene for its sequel, “Same Old Game!” So with the early history of Barings now assimilated, I went back, or rather forward to the story that triggered my interest in the first place, and returned to Lord Revelstoke - Edward Charles Baring, who had acquired the Membland Estate in south Devon in 1877, whilst he was senior partner of Baring Brothers Bank. His cousin and fellow partner in the Bank, Henry Bingham Mildmay, had acquired the adjacent estate of Flete the year before. The two men had married, by coincidence it seemed, sisters who had grown up at Flete before the estate (and that of Membland) had been lost to their family through some distant financial disaster. The question of why the two London bankers would marry the two Devon sisters was still hanging when I read more of the Barings Bank crash of 1890 – the one that preceded the Nick Leeson affair by almost 100 years, and in its time of equal magnitude, if not with quite such devastating results. Barings Bank crashed in 1890 because of one speculative investment too far in Argentina – the partners seemed somehow distracted in Devon. Only reluctant but decisive action by the Bank of England with support from, amongst others, Lord Rothschild saved a run on the world’s Banks. Barings was a private merchant bank and its liability was unlimited. The quid pro quo imposed by the Bank of England on the partners, in particular Edward Charles Baring and Henry Bingham Mildmay, was draconian – in effect putting both men into bankruptcy, and requiring the disposal of the Devon estates, the Mayfair townhouses and the sale of their sumptuous contents. I have attempted to describe what has become known as the “Baring Crisis of 1890” together with the stories of the four very different families that came together to participate in a real-life Victorian melodrama, complete with its a tragic finale. To do this I have split the book into three parts. Part 1 chronicles the families, Barings, Bulteels, Binghams and Mildmays; Part 2 the ”Baring Crisis” itself, and Part 3 deals with the aftermath of the event. I have attempted to keep the story flowing to make to make it easier to read. However the wealth of background research that has been assembled cannot be ignored, so for more information on any aspect of the story, hopefully you will find it the “Notes and Sources” section that is classified by chapter, or in the appendices. Barings Bank did recover from the crash of 1890, only for history to repeat itself almost 100 years later, when Nick Leeson killed it off once and for all, after the lessons learnt at the end of the nineteenth century had long been forgotten. If you do ever get to walk the carriage drive at Noss Mayo in Devon you will you will know who built it and what became of him! And here it is – I hope you enjoy “Same Old Game!” as much as I did researching and writing it!

The cartoon by John Tenniel that was published by Punch on Saturday November 8th 1890, the same day that Lord Revelstoke met the Governor of the Bank of England, William Lidderdale to discuss Barings' plight. The reality of Barings dire circumstances was known to very few people when Tenniel drew this cartoon and Punch published it. Whoever tipped off John Tenniel was very well informed................

SAME OLD GAME!"

Old Lady of Threadneedle Street - "YOU'VE GOT YOURSELVES IN A NICE MESS WITH YOUR PRECIOUS SPECULATION! WELL - I 'LL HELP YOU OUT OF IT, FOR THIS ONCE!!"

I have explored the mystery of the the source and the intriguing timing for this Punch cartoon, and "Mr Punch and the Crisis of 1890", a chapter from "Same Old Game!" follows……………..I have explored the mystery of the the source and the intriguing timing for this Punch cartoon, and "Mr Punch and the Crisis of 1890", a chapter from "Same Old Game!" follows…………….."and Mr. Punch"

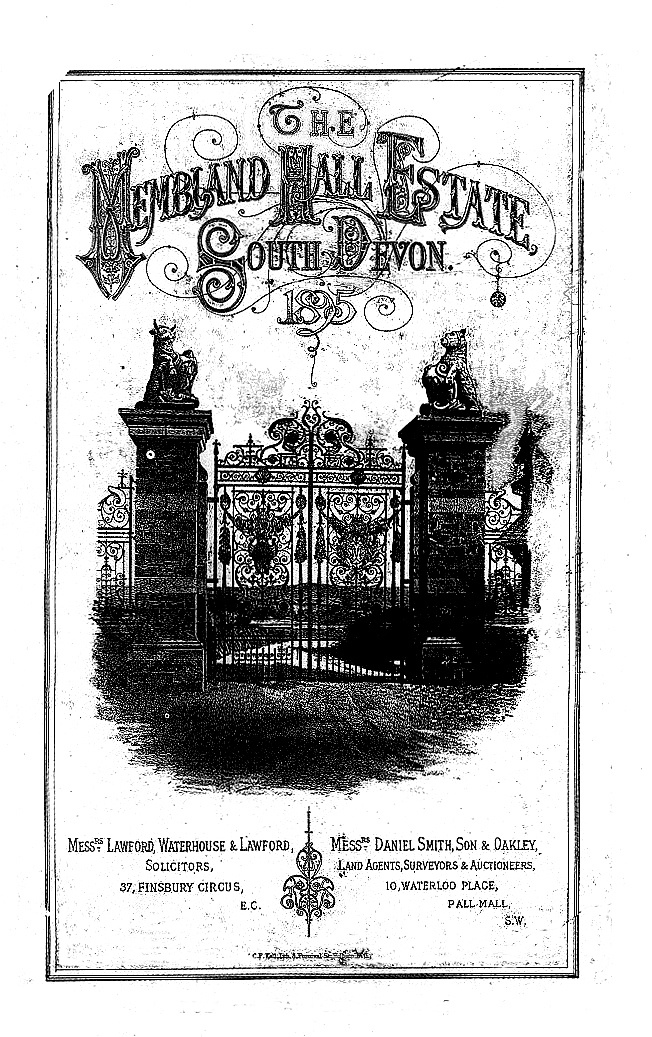

From the sale catalogue for the Membland Estate of Edward Charles Baring, later Lord Revelstoke, from 1895. Barings Brothers Bank collapsed in November 1890 and was saved by the Bank of England and a consortuim of city banks, most notably Rothschilds. The quid pro was that Revelstoke and Henry Bingham Mildmay must offer up their estates to the Bank of England. Membland was eventually sold to a shipbuilder from Hartlepool. The estate was broken up and much of it was sold to the existing tenants. Membland Hall itself and all its memories were literally blown up in 1928. The neighbouring estate of Flete was leased but not sold and now remains in the Mildmay family to this day.

Return to "Books"...................

I thought that "Same Old Game!" was my last opus on the Baring family. Imagine my surprise as I started the research work on the up-coming "Winterbotham, Cotton and Miranda" to come across Lord Revelstoke's bookish son Maurice in a context that I wasn't expecting - the establishment of the Royal Flying Corps in 1914.

"Make a note of the Baring!" appears below

All Rights Reserved © David Tearle 2023

“MAKE A NOTE OF THAT, BARING”

In my book “Same Old Game!” about the “Baring Crisis of 1890”, I included vivid descriptions of the life of privilege lead by Lord Revelstoke and his family, written by his son, the Hon. Maurice Baring. Maurice Baring was the second youngest of Lord Revelstoke’s (Edward Charles Baring) sons and was born in 1874. He grew up in the family homes in Charles Street, Mayfair, Coombe near Wimbledon and later at the 4000 acre estate at Membland in Devon.

The Barings Bank crash of 1890 was devastating for the whole family but none more than Maurice, who was just 16 years old at the time. Whilst his siblings went on to greater things in the re-constructed Bank or in politics or married well, he ploughed his own furrow as a journalist and writer, in which he was able to exploit his remarkable and extensive language skills. He was fluent in most European languages and spent a number of years in Russia before the revolution. He later became quite well known as a writer and novelist with a substantial body of work, but he is now largely forgotten. In 1912 he wrote a memoir of his early life, “The Puppet Show of Memory”, and I included extracts relating to his early years as a scion of the Baring family as an appendix to “Same Old Game!” Well worth reading, both the book and the appendix!

I was not expecting to hear or write about Maurice Baring again, since my current research relates to “Winterbotham, Miranda and Cotton”, a history of the development of photographic intelligence by the British secret serice before the Second World War. Whilst gathering information on photographic reconnaissance during the First World War I came across a slim volume entitled rather cryptically, “RFC HQ” written by a Major Maurice Baring. “RFC HQ” is not a fragment of code but a personal account of the creation and development of the Royal Flying Corps from September 1914 right through until the Armistice in November 1918. Could Major Baring and the quiet novelist be the same man. Surely not?

In the summer of 1914, the 40 year old Hon. Maurice Baring had been in Russia, but as the possibility of war with Germany started to become a probability he hurried back to London, concerned that he should do something to help the war effort. As might be expected of a member of the Baring family, he did not report to a recruiting office but when war was declared on the 4th August presented himself at the War Office to Brigadier General Sir David Henderson, whom he had known for many years. Maurice Baring was aware that Henderson was currently director of military training with a very distinguished service history since being commissioned in 1882. He may not have known that in 1908 Henderson learnt to fly, having observed the Round Britain Air Race of that year. Unlike the rest of the military top brass Henderson was immediately convinced of the potential of the aeroplane in tactical reconnaissance.

The Government’s reluctance to engage with the development of flying machines in the face of the threat from Imperial Germany lead to increasing concern from the public and the press. In response the Government asked the Committee of Imperial Defence to consider the possibility of establishing an aviation service. A sub-committee was appointed in December 1911 to examine and report on the matter. Henderson was one of three officers who recommended the formation of a dedicated air corps. This was approved and Royal Flying Corps was formed in April 1912.

Henderson returned to his role as a staff officer, and was appointed director of military training, with ultimate responsibility for the new aeronautics branch. In September 1913 a new department of military aviation, including the Royal Flying Corps, was established under Sir David Henderson, and this was the state of affairs when Maurice Baring presented himself at the War Office in August 1914.

Baring suggested to Henderson that with his grasp of six European languages, in particular German and Russian he might be suitable for a role as an interpreter with the British Expeditionary Force in France; General Henderson thought an office job at home might be more appropriate but he “would see what could be done”. After several days Maurice Baring received a letter from Henderson advising him that he was now on a waiting list, and on the assumption that was the end of the matter he considered returning to Russia.

But this was the moment when the War Office decided that General Henderson was to take, with immediate effect, personal charge of the RFC in France, in addition to his supervising role at home.

On Saturday 8th August Baring received a personal note from Henderson informing him that he would be going to France with him, again with immediate effect. He would be a Lieutenant in the Intelligence Corps attached to the Royal Flying Corps.

On Tuesday 11th August Baring left Newhaven for an unspecified location in France as part of the advance party to establish the RFC, which at that time had assembled four squadrons, of which three would be attempting the perilous flight to France. General Henderson and three staff officers joined them at Amiens a few days later.

Lieutenant Baring was at General Sir David Henderson’s side and witnessed the first faltering steps in reconnaissance, bombing and air combat and its exponential growth thereafter. In August 1915 Henderson was recalled to London and replaced by Colonel, later General Hugh Trenchard, who took on Major Baring as his “private secretary”, initially “on probation” They were to stay together until November 1918, by which time the RAF had been formed from the RFC and the Royal Naval Air Service. Baring was always at Trenchard’s side as he toured the squadrons – “Make a note of that Baring!” was to become a catchphrase throughout the RFC.

General Sir David Henderson is now considered to be the “father of the RAF” and General, later Air Marshal Hugh Trenchard kept it alive through the 1920’s and managed its rapid growth in the 1930’s. In the autumn of 1914 the RFC had 146 officers and a motley collection of already outdated aircraft. By November 1918 the RAF had 27,000 officers, 250,000 other ranks and over 22,000 aircraft spread over 188 squadrons.

Maurice Baring had served from the first day of the Great War until the last. If he had not been pressured to write his experiences as “RFC HQ” he would probably have not mentioned it again. He returned to life as a novelist and died in 1945 convinced that he was going to be bombed by the Luftwaffe.

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/7485881-flying-corps-headquarters-1914-1918

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/7485881-flying-corps-headquarters-1914-1918

All Rights Reserved © David Tearle 2023